|

19-Feb / 0 COMMENTS

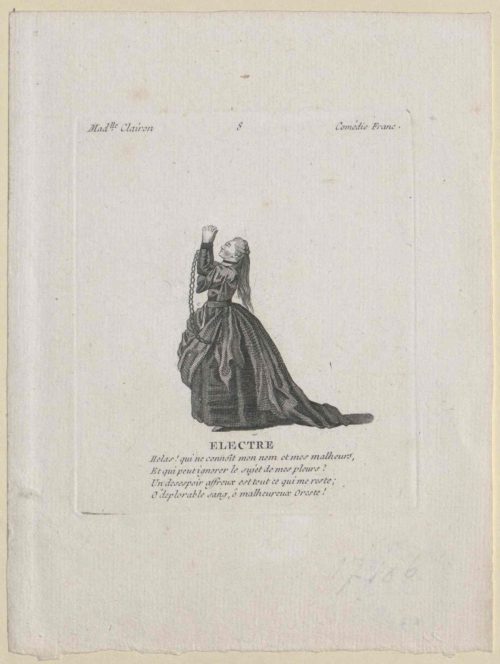

In this moment in the public discussion that some call a watershed, I wanted to weigh in with an account from the memoirs of Hyppolite Clairon, one the greatest tragedians of the 18th century. Her memoirs, written at the end of her life, and published immediately in German, English and of course French throughout Europe, shed light upon her self-developed craft, as well as on the state of the actor and theater in society at the time. Alongside her description of what happened to her when she was just fifteen, strike me especially her attempts to explain her reactions at the time- her silence, and the relation of how it affected her everyday life and her work.

Memoirs of Hyppolite Clairon, the celebrated French actress: with reflections upon the dramatic art: written by herself. Translated from the French in two Volumes. Volume 2 of 2 (London 1800)

Pg. 44-52 “A poor pleasant devil* (His name was GAILLARD.), who wrote verses, and picked up a supper as well as he could, obtained leave of the ladies to come sometimes and amuse them. I was daily the subject of his couplets and stanzas, in which Venus and Vesta were nothing compared to me. But while he was praising my charms and my virtue, he was planning how he might enjoy the one, and destroy the other. Knowing perfectly the nature of the house he took the opportunity of my mother’s absence, and persuaded an old servant we had to let him into my chamber. It was about nine in the morning, and I was still in bed: I was studying- the weather was warm: I had not heard the slightest noise to induce me to be upon my guard. I was just fifteen years of age; and my chemise, and my hair, which flowed in ringlets, were the only covering that concealed me. This sight did not long leave him master of himself: he ran and endeavored to seize me in his arms. I had the good fortune to escape. My cries brought up the servant, and a woman who lodged in the house. We got brooms and shovels, and drove the wretch into the street. When my mother returned, she determined to lodge a complaint against him. He was reprimanded by the magistrate, had ballads made upon him and sung through the city, and he was ever banished [from] our house. But rage succeeded his love and desire; and he wrote that disgusting libel against me, which has been since circulated throughout Europe.

I was at Havre de Grace with the company, when it first made its appearance. Far from my protectors, I knew not how to act. Not daring to trust to the advice of the ignorant, the brutal, or the indifferent, I took no step to point out to the public the malignity of the work. My own candor induced me to believe that I might trust to the justice of mankind. Had I been more experienced, what could I have adopted? A few months imprisonment, to which the wretch might have been sentenced, would not have prevented the publicity of the book; my pretended shame would not have been less talked of in the world; and the reparation made me by the laws would have been overlooked. However, I am now convinced that I acted wrong in not appealing to the laws against him. But is it right, that without regard to the age, the inexperience, or the inability of the oppressed, the tribunals of justice should wait for the complaint of the individual injured, in order to afford reparation? The libelous and calumnious tendency of the book, the perusal of which modesty could not avow; the author, by his audacity in publishing it to the world, with his name prefixed, having drawn upon himself that public indignation which forced him to be concealed from notice; the complaints which I had previously made of his criminal attempt upon my virtue; my youth, and my absence from the scene of my supposed vices; – all these must have appeared to everyone sufficient refutations of so unfounded and unjust a charge. Should the want of a vain formality, which my ignorance and inability prevented me from resorting to, have withheld the justice of those who called themselves the interpreters of the laws, the defenders of mankind, and the avengers of innocence. I was unsupported, and could do nothing of myself. This was my crime, and my misfortune.- Alas! of what consequence is it to the majority of mankind, that an individual is wretched? I now am sensible, by experience, that they delight in seeing their fellow- creatures suffer. Their levity will not allow them to investigate; their malignity and self-conceit make them disregard the despair of our sex. However improbable the scandalous reports against us may be, their own perverseness of disposition induces them to believe them; and the impunity of which they are certain increases the audacity and cruelty with which they confirm the slanders against us. Though they may have neither seen or known anything of the matter, it is so said, or there’s such a report, – that’s quite sufficient for them. What do they gain by this? To embolden the calumniator, and, perhaps, become victims in their turn, if chance places them before the eyes of the public, by calling them to the exercise of any administrative or magisterial functions. The libel which was directed against me is now lost in the immense number of those which have been directed against the whole world. Innocence, majesty, the divinity even, are no longer sheltered from the shafts of malice: the atrocious libels I have read against them ought, assuredly, to console me for what I have read against myself.

But I was far from deriving consolation from my reflections at the moment I received the injury. I returned to Rouen with fear and trembling. I imagined that every door would have been barred against me. I did not dare to lift my eyes to any one; and I appeared upon the theater with dread; but I found the same public and the same friends. The respectable lady, who had so eminently befriended me, opened my eyes as to the cause of my misfortune. I perceived I was indebted for it to the misconduct of my mother; and the knowledge of this inspired me with so great an aversion for her, that it was with the utmost violence to myself I could submit to remain with her till her last sigh. I have since surmounted the impetuosity of my character; and perhaps I am entitled to claim some credit for the silence I preserved on the occasion, and for the happiness she continued to enjoy.”